Filled with breathtaking challenges that have tested our faith and endurance, 2020 has been a year like no other. But, depending on the lens you look through, the pandemic, protests, polarization, misinformation and other maladies we are living through might simply seem like incidental variations on centuries-old themes. Among this turmoil, the tools of an artist can dissect the complexities of the present and connect it to the past. Inspired by their island heritage and history, Caribbean-American artists continue to make Caribbean art during COVID-193, producing work replete with lessons and stories of survival. We talked with four of them about how their creative process has evolved to meet the times and how 2020 has reshaped their sense of purpose.

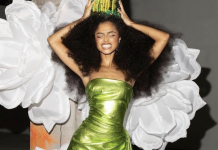

Embrace The Process | Vickie Pierre

The pandemic set in just as mixed-media artist Vickie Pierre was completing a residency. “I was deadlocked. I didn’t want to get in my car. I didn’t want to be in my studio,” she said, describing those first few days back in Miami. “Creatively, I was stunted. I didn’t work for about two months.

“Then the murders started happening,” Pierre said, referencing the police killings of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and others. “And then you’re just left shocked and immobilized.”

Pierre focused on completing pieces for a scheduled exhibition at the Fredric Snitzer Gallery in Miami. Part of an ongoing series, “Poupées in the Bush” is a surrealistic exploration of abstract Black female bodies adorned with gold leaf, flowers and elements of tribal dress. She also tried to complete works that focused on race, ethnicity and the Caribbean ― but she was stuck.

“My mind was really on what was going on and not really on how to resolve these pieces,” she said. “I realized it was because I needed to do something about that feeling of anger and sadness.”

So, she created a new installation: “Black Flowers Blossom (Hanging Tree).” It pulls ideas from her brainstorming notebook and from her thoughts about this tense, painful moment in American history. “I wanted to do a work that spoke to these deaths, systemic racism and historical racism, and how it affects just the general atmosphere,” she explained.

Pierre pulled imagery from multiple historical periods and places as a “nonlinear recognition of what’s going on,” and as representation of “a collective history.” This new direction proved challenging for her, in part, because she’s not comfortable using overt racial imagery. In most of her work, meaning lies just below the surface. Incorporating these more visceral fragments of the past felt necessary, she argued, to show that our identity is shaped, in part, by history.

In Pierre’s personal life, that history includes growing up in New York with a Haitian family speaking English and Creole and the new-to-her sense of community pride among Miami’s Haitian residents.

“I never thought of myself as a Caribbean person. I thought of myself as a New Yorker; I thought of myself as Black. That’s how I existed in New York,” she said. “Coming to Miami, the Caribbean is so prominent. It’s something I’ve sort of slowly integrated into. The funny thing [is], I feel like it was always present in my work in some way, but I never recognized it and acknowledged it as such.”

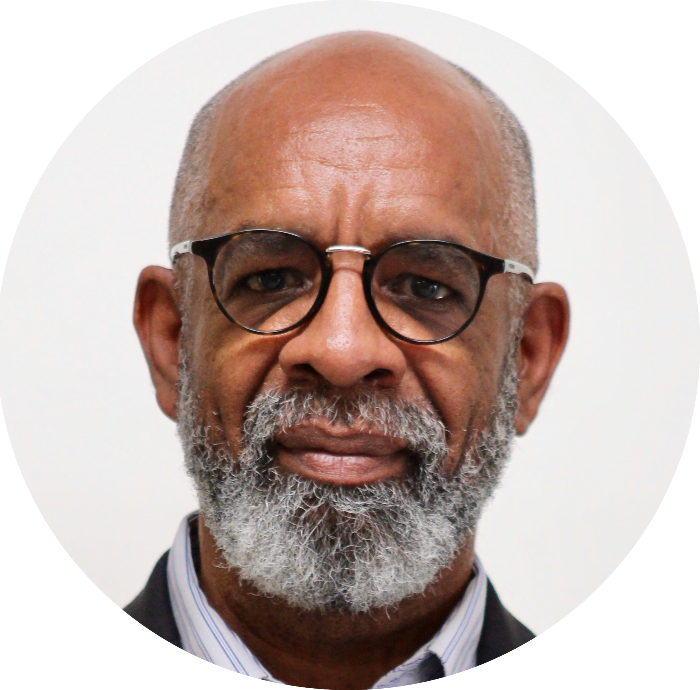

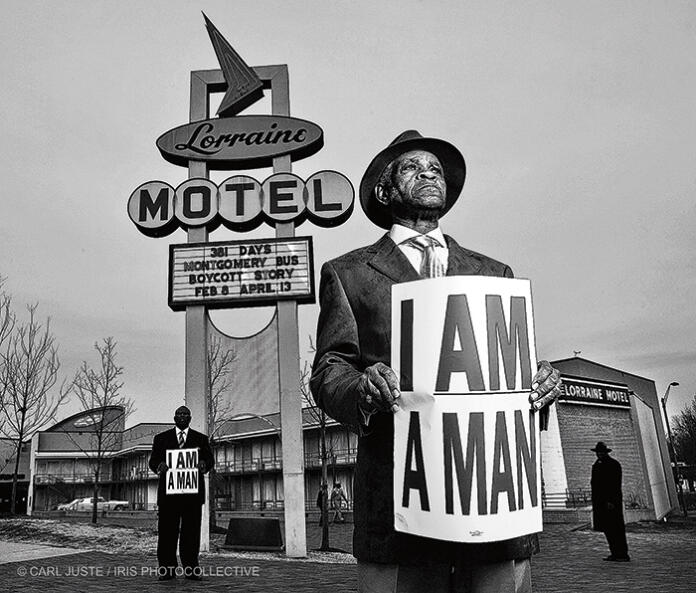

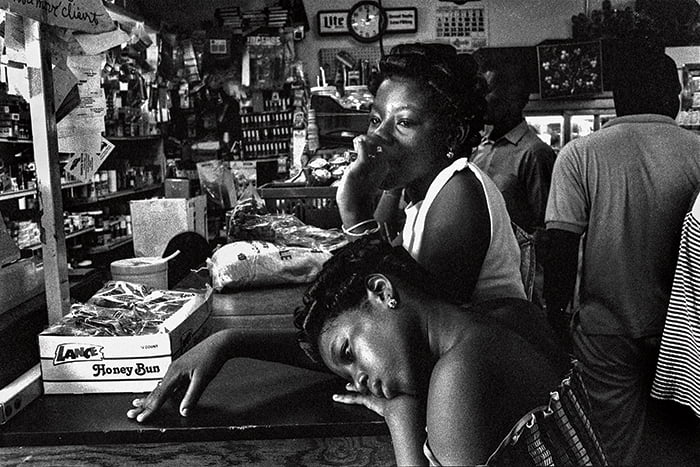

Surviving Together | Carl Juste

The phrase “new normal” — a term bandied about to describe the crises of 2020 — never sat well with Miami-based photographer Carl-Phillipe Juste. He has spent a career chronicling society’s most vulnerable as a photojournalist for the Miami Herald and as an art photographer exploring communities around the world.

From where he’s standing, “there is no ‘new normal’ [because] nothing has ever been normal. Normal is the luxury of the rich and the privileged. Most of the people on this planet are not privileged. Most of them probably don’t have a home where they feel safe, or an environment which they can control.”

Uncertainty is familiar terrain for Juste, who fled with his family in 1965 from political persecution in Duvalier-ruled Haiti. Instead of despair, Juste learned from his parents’ response to upheaval, that we find resilience and hope only when working together. He saw this firsthand watching his parents Viter and Maria Juste become powerful advocates for Miami’s growing Haitian refugee community in the 1980s, in what would become Little Haiti.

The result, for him, became an intense appreciation for the importance of community. “We get to believe the individual is so powerful it can control all circumstances. It cannot. No one comes on this planet alone,” he said. This collaborative spirit continues to feed his work, starting with the Iris Photo Collective ― an organization he founded to bring together artists of color to tell stories about their communities, which are too often ignored in the public eye.

Responding to the unique turmoil of now, he has directed Exile At Home, a series with WLRN and Miami Book Fair featuring still images, video and written narratives collected from people who shared their experiences with COVID-19. Another collaboration, Imagined Visions of Hope, featured small collections of photographs submitted by artists from around the world that the group hopes to exhibit on five continents. Juste is also one of seven photographers from Florida, Oregon, New York and Washington, D.C. contributing to Defiance ― a project inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, and for which they hope to secure funding to display in February.

Little about 2020 has changed his photography, which looks toward the possibilities of the future even as he dissects the present. “For my process, I’m interested not about me,” he said. “I’m more interested in what other people think about the same subject because then I have something to engage with. I want people to talk to each other. I don’t want people sitting there trying to think how I was thinking or how I was feeling. I don’t go around asking what I am, I go around asking why it is.”

Lessons from the Past | Basil Watson

Simmering with frustration and hope, a crowd stands tall with fists raised high in Jamaican artist Basil Watson’s bronze tabletop sculpture, “Boiling Point.” Among them, one figure steps forward and points to a better future, looking back as if urging the others to join him. Depicting the resilience of the human spirit, this piece resonates with current, guttural public cries for change. Incarnating the spirit of 2020, it reflects attitudes toward the nationwide Black Lives Matter protests against police brutality, the public health fight against the COVID-19 pandemic that disproportionately kills Black Americans, and the heated presidential election that exposed the nation’s economic and racial divides.

But Watson made “Boiling Point” in 1986, not 2020. The piece was inspired by the fight to end Apartheid in South Africa.

“[These are] things we are discussing today and have discussed for decades,” said Watson, who now lives in Atlanta. “It focuses on protest, on sacrifice, [and] on leadership.” It’s the enduring poignance that inspired him to find funding and a public home for a large-scale version of the sculpture, specifically at a location where victims of police brutality were killed.

Creating such monuments to what Watson calls “the heroic in mankind” has been a central focus throughout his remarkable career as a sculptor, known for his expressive approach to the human figure. His works include public commissions in Jamaica, depicting national luminaries like Usain Bolt and Louise “Miss Lou” Bennett-Coverley.

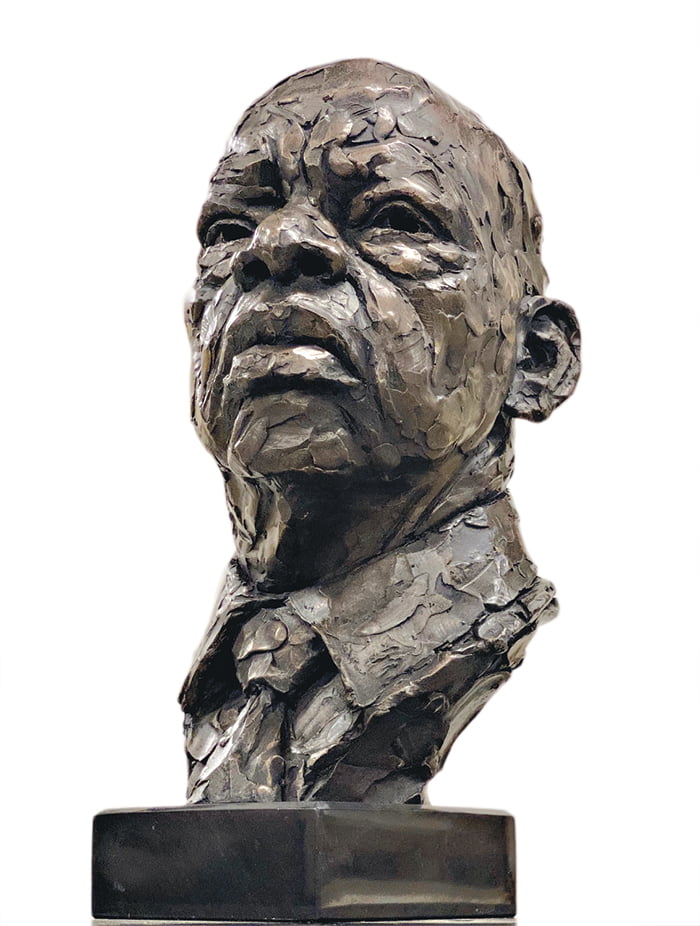

His most recent projects turn to heroic figures from his adopted city Atlanta: from a personal project sculpting a bust of civil rights activist and U.S. Representative John Lewis to a towering commissioned statue of Martin Luther King, Jr., greeting visitors outside the Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta.

Such work exploring who we honor, and why, feels perfectly suited for this moment in history. To Watson, American public sculpture has often been valued primarily for its artistic merits detached from intended themes or historical context. Now, a growing movement has demanded public artworks — in particular Confederate monuments — be weighed in their complete social context.

“With all my time at home, with the pandemic and social protests that have been taking place, it has focused my attention on social issues that have been with me for my entire life,” he said. “Martin Luther King Jr., for instance, when he was killed I was [about ] 10 years old. Growing into my teens, the effect of that on the world and Jamaica was strong.”

This influence of Watson’s heroes “was always there,” he said. “But I think the recent past has refocused on a lot of those issues. ”

The Audacity of Joy | Nate Dee

In 2019 (when viral pandemics were only the stuff of cinematic nightmares), painter and muralist Nate Dee found himself visiting his parents’ native Haiti, participating in the Port-au-Prince mural showcase Festi Graffiti. Something clicked as he walked through the event. Surrounded by the vivid hues of Haitian public art, he realized that his parents’ homeland had quietly affected his own artistic approach ― that there is something uniquely profound about artists bringing joyful color to places and people that need it.

“Traditional Haitian art is very vibrant and very bright even when they’re discussing things that are heavy and grim,” noted Dee. In his earliest days as a graffiti artist, the Fort Lauderdale-based painter discovered the power of color, which he translated into his current paintings and murals filled with chromatic, mythical figures.

Right now, this feels more true than ever for Dee, whose full name is Nathan Delinois. The color-driven perspective inspired his latest collaborative project with fellow Florida artist, Mojo ― a mural in Miami’s Brownsville neighborhood that they titled, “Know Peace.”

The work offers “a different take on what activism might look like and what resistance might look like,” he explained. “I saw this quote that was something like, ‘Just to be happy in these times is an act of resistance.’ We wanted to create a mural that was a nod to what’s going on, but also focused on the other side of that: holding on to your happiness, holding on to your love and holding on to your joy.”

This year has inspired a subtle shift in Dee’s creative process. He now feels drawn to create more public art rather than small individual paintings because these “would have the biggest impact.” Events like the Black Lives Matter protests have inspired him to reflect on how he approaches themes of identity in his works and the purpose of his public art.

Dee hopes his colorful works draw viewers into reflection on the grand themes of life rather than tying directly to a specific instance in time or making a particular declaration. Yet, the death of George Floyd spurred him to directly address the world. Drawing inspiration from the Spray Their Name campaign in Denver, Dee also designed a print work and donated his profits from it to the cause.

He believes these unique opportunities provided by public art projects spark conversation, whether that’s how a neighborhood views itself or how the work communicates to the larger world. “You’re creating a dialogue among people who aren’t always heard, or who don’t always have access to the conversation,” Dee said. “Public art is a way of organizing and creating open dialogue with people.”