The power of social media is undeniable. We saw it used as a political tool during the 2008 election, where Obama successfully catalyzed an audience of voters using Facebook as a campaigning tool. More recently, we also saw the power of social media in political organizing when white nationalists used various social platforms to organize an occupation of the Capitol Building in Washington, D.C. In 2019, Facebook users watched in shock as someone livestreamed the shooting of multiple people in a mosque in Christchurch, New Zealand.

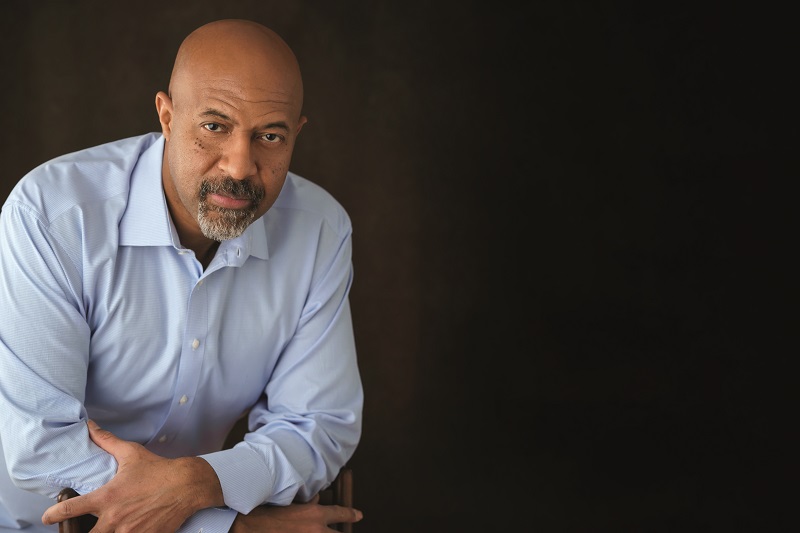

To combat the negative, individuals, organizations and even corporations are starting to take a proactive approach to censoring hate speech and violent organizing in social media spaces to protect civil rights online. These instances prove that social media, as a tool, has a great capacity for both positive and negative influence. I had the chance to speak with Roy L. Austin Jr., VP of Civil Rights and Deputy General Counsel at Facebook, who hopes to do just that.

Austin has a long history of civil rights litigation that spans decades. His experience in the field includes time spent as a trial attorney with the criminal section of the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Department of Justice, as a senior assistant U.S. attorney in the civil rights unit of the D.C. U.S. Attorney’s Office, as a deputy assistant attorney general in the Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division, and as the deputy assistant to the president for the Office of Urban Affairs.

One of his most noteworthy accomplishments was co-authoring a report on Big Data and Civil Rights, where he worked with President Barack Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing and helped develop the Police Data Initiative, which has been influential in pushing for data transparency in law enforcement policy nationwide. He was also a member of the president’s My Brother’s Keeper Task Force and most recently worked as a partner at the law firm of Harris, Wiltshire, & Grannis LLP, specializing in criminal defense and civil rights law.

Equal Footing

When I ask how someone with such an auspicious career got into the field of civil rights, Austin chuckles. “The shallow truth is that my parents, as wonderful as they are, allowed me to watch way too much TV as a kid.” He admits, “L.A. Law was the [show] I really fell in love with. The idea of being a stand up attorney was something that I dreamt about as a child.” Austin was also watching something else from the comforts of his home in State College, Pennsylvania: the nightly news.

“I grew up as a Black kid in an almost exclusively white community, and [I came to] a realization primarily from the media that my life was very different from other Black kids growing up in the world.”

He recounts watching “image after image of young Black kids being shot, killed, arrested,” and the impression that had on a child whose biggest problems were finishing his homework and attending college football games.

Austin, whose Vincentian father was a criminologist, sociologist and U.S. ambassador to Trinidad, endeavors to follow a path similar to his dad’s. He notes, “A goal and passion of mine is to make sure all kids grow up with all the opportunities that I was afforded.” Austin says that his upbringing was deeply rooted in the Caribbean culture of his parents. He relates that his parents “did everything they could to make sure that we understood Caribbean culture and life. It was just a regular part of who we were, from celebrations to food to family to friends.”

He reflects, “My entire life was built on my parents’ heritage,” and he attributes his success to them. “I am grateful for my immigrant roots. [They] gave my parents motivation to make sure that their children were put in the best possible positions because they remember what it was like to grow up in a place where they didn’t have material goods and didn’t have access to top resources.” He connects this to his personal need to strive for better conditions for all people, regardless of identity.

Same ****, Different Day

When it comes to his work, Austin continues to grapple with the concept of civil rights in a digital space. Even though most social media companies have large teams devoted to security and monitoring, these teams predominantly use algorithms that often replicate the biases of the people who create them. Many companies have looked to promote diversity in cybersecurity positions, but according to Austin, this is an area that is still evolving.

“We are dealing with machine learning and algorithms, and that’s a space that civil rights law has never really looked at. How do you make sure you are respecting cultural traditions, religious liberty, freedom and respecting all voices?”

It brings up ethical questions that have been part of the broader conversation surrounding the media and free speech for years. “Look, it’s social media, so a piece of that is the same kinds of questions that are raised about all media, all conversations. What’s appropriate, what’s inappropriate, when does language cross the line from poor speech to hate speech or bullying?” He relents, acknowledging that regardless of technology, there are broader questions we have to answer for ourselves as a society.

For Austin, diversity in this arena is a start, but it is not enough to combat the intersecting systemic issues that marginalized people face. Without a focus on equity and justice in the real world, issues of the American political system proliferate on these social media platforms.

According to Austin, one of the events that made this glaringly obvious was the pandemic.

“The pandemic has shone a light on the challenges that the world faces. Those who have [privilege] get access to resources, access to the vaccine, access to quality news.” It has shown us that, “Poor Black and Brown communities are still struggling. Again, it’s a reflection of where we are as a world, as a country.” We as a country have a long way to go in our efforts to fix these issues, and social media mirrors that. Still, we must work toward providing safer spaces that people can inhabit without having to endure virtual, emotional or physical forms of violence and marginalization.

The Great Unknown

So what’s next? “That’s the thing about this field,” Austin admits, “I have no idea where we are going next. The field of technology is moving so quickly. Virtual reality glasses, the power of self-driving cars — they talk about things that were, for us, science fiction, that I see happening in our lifetime. What is important is that, hopefully, my team and I build an infrastructure for whatever comes next so that people are not discriminated against.”

For Austin, it is about taking a structural approach and building out systems that take into account diversity, equity and justice, serving generations to come. Social media will continue to play an integral role in the lives of future generations.

As we close our interview, Austin reflects on his own experiences as a father of two children. I ask how we can teach young people to navigate spaces like social media, where they are at risk of encountering negativity. “I think you instill in your children — especially young Black children — resilience and the ability to take on all that comes to you, the wherewithal to fight back and to stand for yourself. That’s what I instill in them and hopefully, whatever the world looks like in 10 or 30 years, they can adapt those lessons wherever they go.”

* The original title of this story was Civil Rights in Cyberspace.