The Taino peoples, the Caribbean’s first inhabitants pre-Columbus, have long labored under the illusion of extinction. Any Caribbean child will remember textbooks speaking of the region’s natives as a bygone culture. The Smithsonian seeks to break that narrative with a landmark exhibit called Taíno: Native Heritage and Identity in the Caribbean. Produced by the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian and the Smithsonian Latino Center, the exhibit explores the Taino’s history and their lasting cultural legacy in the region. The show also highlights the modern-day descendants and their contemporary and passionate efforts to keep Taino traditions alive and vibrant.

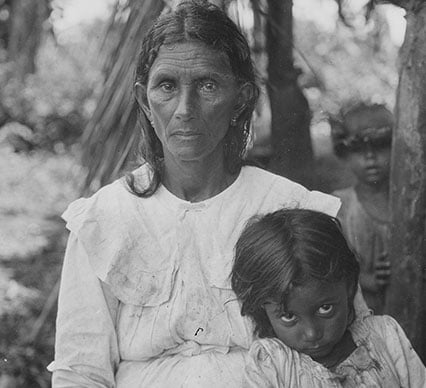

Photo by Mark Raymond Harrington, 1919. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution. (N04469)

The Taino civilization concentrated through the Greater Antilles, with large populations in Cuba, Jamaica, Hispaniola (today’s Haiti and Dominican Republic) and Puerto Rico. Today, a growing number of people have reclaimed their indigenous roots, preserving traditional practices passed through generations, and advocating for visibility. Such traditions include creating dishes like the “casabe” or “bammy,” a flat bread made from cassava. Tradition building methods were also preserved like the bohío, a structure made from local materials resistant to weather. Others also explore the Taino roots of common words like hammock and hurricane.

“In the last 20 years, a lot of Caribbean folks have said, ‘where’d this movement come from? History books tell me the opposite,’ and yet everybody who is Native has family stories and connections,” says curator Ranald Woodaman in an interview with Smithsonian Magazine. “This is a complicated story because in many ways we are reframing histories like survival and extinction. We’re saying that we can survive through mixture and change.”

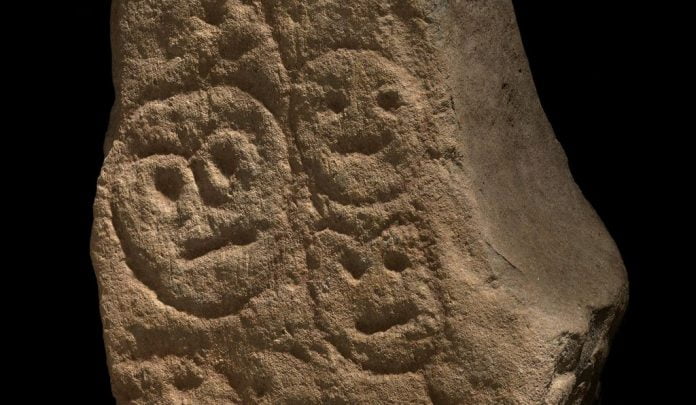

To honor both the past and the present, the exhibit ranges broadly, from pre-Columbian sculpture pulled from the Smithsonian archive, to artwork from the popular superhero comic “La Borinqueña,” which prominently features Taino iconography.

The show will run through the end of October at the museum’s George Gustav Heye Center in New York City. If you can’t make it to New York, check out this special chat with the exhibit curators Woodaman and Jorge Estevez of The Museum of the American Indian.