For Caribbean people, discovering what it means to be Black in the United States is a rite of passage—that perspective-shifting moment when you realize that, unlike the warm and welcoming way your loved ones see you, society sees something very different in the color of your skin. My journey to this moment was a roundabout one. Before I had the chance to become aware of what it meant to be Black and American, my parents packed up our home in New York City and moved us to Jamaica. I was just 5 years old, and my brother was 7.

Veiled Reality

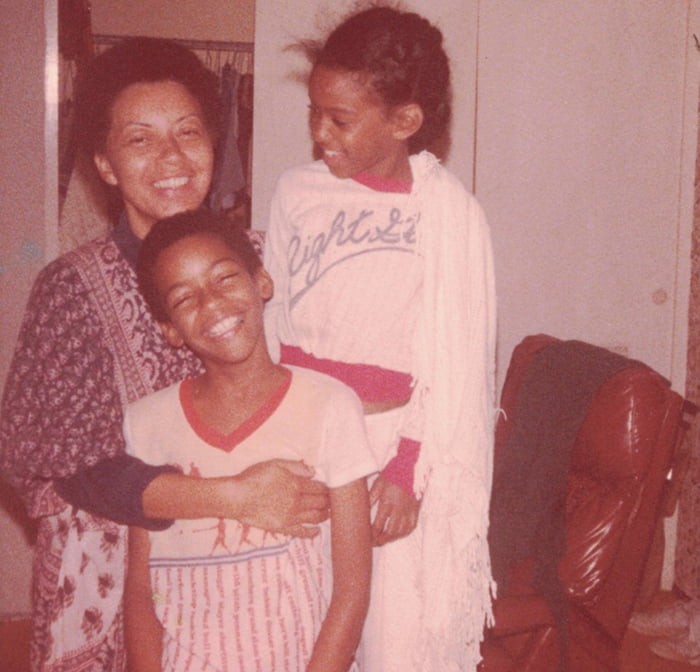

In many ways, our Jamaican family life shielded us, kids, from American racism. My parents had given me an Ethiopian first name and filled our home with books and imaged by Black people. My mother bought me delicate gold chains and gasped at how lovely they looked on my skin. And when I requested a Baby Alive doll for Christmas, I didn’t get the blond-haired, blue-eyed one from the commercials. I got the brown-skinned one my father said looked beautiful, just like me.

However, a form of anti-Blackness lurks as an undercurrent throughout Caribbean societies. I learned of aspersions that would be cast upon me based on the color of my skin—that my mother’s much lighter tone was celebrated here, and, contrary to what she was teaching me, my complexion was not considered as beautiful as hers. I also learned that my long wavy hair and any hair textures that departed from the tight curls of many Black people were valued more. Even so, the very fact of our Blackness did not impact our success or safety here. Every racial background was part of the melting pot, and nothing in Jamaica made me feel that being Black would disadvantage me in any material way.

But at my young age, I may not have seen the full picture. So many darker-skinned people in the West Indies do find that their skin color is an impediment to upward mobility.” Racial issues often get masked in the Caribbean as class issues, ”explained Professor Kimberley D. McKinson, an anthropologist at the City University of New York. “Why is it that the poorest in the Caribbean society are all Black, and the more [light] you get, the more socially mobile you become? Even if we mask it as uptown and downtown, these valuations of race and color are inherently mapped onto these supposedly class[-based] categories.”

Rites of Passage

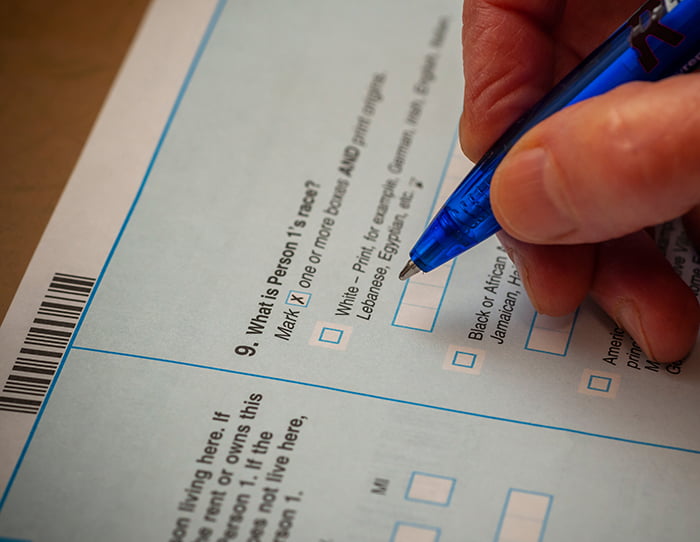

My perspective changed when I returned to live in New York City ten years later. Here, Blackness meant accepting that the faces of alleged criminals who bore my skin tone and who were assumed guilty would regularly be plastered across the nightly news shows. It meant the white lady would wind up her window as my brother crossed the street nearby. Here, Blackness, to the outsider, is dangerous. It’s something to be monitored and policed— the way my new high school registration form requesting my race did.

These constant requests for racial categorization are another troubling Caribbean Black rite of passage. When we come to America, we are confronted with our Blackness in a culture that is consumed with race and has racism at the core of its existence.

Faced with this reality, Caribbean folks have responded differently over time. In the first big wave to America in the early 20th century, island immigrants “very much understood themselves in racial terms of what it meant to Black in the U.S. politically,” explained McKinson. In response to violent mass lynchings and riots burning down Black enclaves, for safety, we rallied behind figures like the Jamaica-born Marcus Garvey, “who in the 1920s articulated and advocated for a universal notion of Blackness.”

By the 1980s, however, “what starts happening is a greater emphasis on ethnicity over race,” McKinson said. “What does it mean to be an ethnic immigrant? It’s to highlight ‘Oh I’m Caribbean; I celebrate Carnival. I’m Black, but I’m from Jamaica.”

Clinging to Multiculturalism

The reason for this shift is perhaps that we’re holding tightly to a little piece of Caribbean multiculturalism—that intrinsic pride we have in acknowledging the races or cultures that are a part of our heritage. “There’s much more fluid understanding of race as it’s socially constructed in the Caribbean,” McKinson said.

Some of my friends agreed. I spoke to Cheddi, who has Indian, African, and European roots. “Mi mix wid everything,” he said. “I could not be lumped into one group.”

For Ann-Marie, our Caribbean “out of many, one people” perspective feels more welcoming. She sometimes feels darker people in America discriminate against her because of her lighter skin and Asian features. “I don’t really feel as strong a connection to African-Americans as I should, mainly because they don’t accept me,” she said. “There’s an inference that I’m not really Black.”

McKinson confirmed her experience: “A big part of race and racialization is not just about how the individual identifies, but how people looking at you identify you.”

Other friends feel right at home is associated with both groups. Joan said she identifies with the Black American experience because “Whites perceive me as Black, not Jamaican.” And David said, “African-Americans are my people; we are one!”

In America, regardless of how we choose to identify ourselves, the status quo places us into one racial category that is arguably the most oppressed group in the nation. My Trinidadian friend Sandra, who embraces being a part of the African-American community, felt the stigma firsthand when she moved to the United States. “I was prepared to be labeled as Black, but I was not prepared for how everything that I said or did was devalued.”

As we struggle with navigating race in this America, we join an even greater struggle that African-Americans have endured for centuries. Whether the Civil Rights or Black Lives Matter movement, this country’s growing pains are our growing pains. At the end of the day, regardless of our ethnic backgrounds, we’re all in this together.