In the Caribbean, a plate of traditional home-cooked food can teach volumes, more than any history book. The history of Caribbean cuisine emerged from a confluence of cultural influences, and centuries of global trading. West Africans brought callaloo, okra, and ackee to complement the tomatoes, potatoes, corn, and beans cultivated by indigenous civilizations across the Americas. Colonial powers brought meats like beef, pork, and chicken, plus staples like oranges, garlic, and onions.

They say too many cooks spoil the broth, but it’s clear our food traditions wouldn’t be the same today without this legacy. Exploring the past and present through the essential flavours and ingredients of the Caribbean eats is a delicious way to learn more about the region.

Salty: Salted Fish

For a boost of protein and flavour, Caribbean cooks have long turned to humble salted fish to create some of the region’s most iconic dishes. Think Trinidadian bull, St Lucian green fig salad, and Jamaica’s national dish, ackee, and saltfish. Salt naturally draws out moisture from meats, making them resistant to mould and bacteria. To “salt cure,” fish would be coated in salt for days and then hung to dry with the help of the wind and the sun. This process dramatically increased its shelf-life, while imparting an intensely salty flavour. For centuries, fishermen around the world have used salt curing methods to preserve their fresh catch.

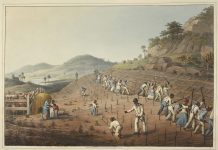

The ingredient became a staple when it was brought to the region through the Triangular Slave Trade between Europe, West Africa, and the Americas. Vessels from Canada, in particular, would supply salted cod, a fish then plentiful off that country’s coast. Plantations relied on the then cheap source of protein as a staple provision for their enslaved populations. It remains an important part of the Caribbean diet. Today, due to cod’s growing scarcity, other types of white fish like pollock and snapper are used instead.

Sour: Tamarind

The most vivid flavour characteristic of the tamarind fruit is its sharp tartness. Indigenous to Africa’s tropical belt, it was introduced to the Caribbean by the Spaniards and Portuguese sometime in the 16th century. Massive tamarind trees now dot landscapes across the region and have attracted a mystique of their own. In the U.S. Virgin Islands, folk tales advise locals to not sleep under their branches. The trees are believed to be haunted, so you shouldn’t sit under their shade after sunset lest spirits follow you home.

The most vivid flavour characteristic of the tamarind fruit is its sharp tartness. Indigenous to Africa’s tropical belt, it was introduced to the Caribbean by the Spaniards and Portuguese sometime in the 16th century. Massive tamarind trees now dot landscapes across the region and have attracted a mystique of their own. In the U.S. Virgin Islands, folk tales advise locals to not sleep under their branches. The trees are believed to be haunted, so you shouldn’t sit under their shade after sunset lest spirits follow you home.

These superstitions haven’t stopped cooks from harvesting the fruit’s culinary potential. Encased in a hard and brittle shell shaped like a bean, the flesh of the fruit adds a welcome complexity to both sweet and savoury dishes. Due to its high acidity, tamarind is a great tenderizing marinade for chicken, beef, and pork. The pulp of the pod is an essential, tangy addition to many popular Caribbean sauces, salsas, and chutneys, and the British adopted it as a key ingredient for their Worcestershire Sauce. To create tamarind balls, a tart candy with an intense combination of sour and sweet flavours, beloved by Caribbean children, the tamarind fruit is rolled into balls and tossed in sugar crystals.

Spicy: Scotch Bonnet

Of all the chilis spicing up island meals, scotch bonnet remains the king of heat in Caribbean cuisine. The popular pepper is used in a variety of Caribbean dishes, adding searing spice to jerk chicken and a low key kick to everyday rice and peas. And this little nugget packs a punch as one of the hottest chilli peppers in the world, up to 140 times spicier than a jalapeño. Available in shades of green, yellow, orange, and red, the scotch bonnet can be finely minced for maximum heat, or it can be added whole for a gentle sizzle.

The name is derived from a Scotsman’s bonnet (also known as tam o’shanter hat) because of its distinctive squashed appearance. The origin of the scotch bonnet is not well known, but most historians trace its roots to varieties from Central and South America, and it is closely related to the habanero variety. Commercially, Jamaica remains the leading exporter of scotch bonnet pepper mash, which is used in hot sauces around the world.

Other, less popular Caribbean chilis with five-alarm fieriness include Trinidad and Tobago’s vibrant red Scorpion Butch T Pepper, and the 7 Pot Douglash known for its chocolate brown colouring.

Sweet: Coconut

Picture a breathtaking Caribbean coastal vista, and odds are a coconut tree that will be part of that scenic view. The tree, however, is equally treasured for its gastronomic bounty. When young, the fruit has soft, gelatinous flesh and is full of refreshing water packed with electrolytes. When the coconut has aged and dried, the flesh becomes hard.

Caribbean foodies take pride in using coconuts at every stage of maturity. But it is perhaps most beloved for its sweet applications. Made from the grated dried flesh, coconut milk adds dairy-free creaminess to desserts like a blancmange, a lush custard particularly popular in Haiti. It’s also an essential ingredient in drinks like Puerto Rico’s pina colada. When dried and shredded, the meat of the coconut infuses a nutty sweetness to other traditional delights like Jamaican gizzadas, tarts filled with a spiced, sticky coconut filling. And it is an essential ingredient in Bajan cookies, a popular savoury dessert steamed in banana leaves. Once made to commemorate the old British colonial celebration of Guy Fawkes Day on November 5, the treat is now popular during the island’s independence celebrations on November 30.

Native to Indonesia, coconuts stand out among common island ingredients for their reputed unique arrival to the region. Scientists believe coconuts came to the Caribbean by riding ocean currents hundreds of years ago.

[…] A report by Attiya Atkins for Island Origins Magazine. […]

Comments are closed.