Sharp suits with cropped “flood” pants. Thin ties with Porkpie or Trilby hats. And Clarks boots, of course ― no exceptions. The enduring “rude boy” silhouette is instantly recognizable to any sharp sartorial eye. Remixing the sleek mid-century fits of American jazz musicians and gangster films, the style evolved into something distinctly Caribbean. Over the years, music legends like Derrick Morgan, Desmond Dekker, The Specials and even Bob Marley in his early days made the look iconic, spreading its influence across the globe.

Photo courtesy of Dean Chalkley

But the fashion figure represents much more than superficial fun. It has a deep-seated history in Caribbean culture. British artist and academic Harris Elliott dissected the rude boy’s cultural impact in his landmark 2014 exhibition “Return of the Rudeboy” with photographer Dean Chalkley. Displayed at the Somerset House in London, the exhibit featured Chalkley’s portraits of contemporary rudies in the city, alongside a chronicle of the style’s influences and evolution.

The show aimed to spread awareness about this “identity and culture without compromise,” says Harris Elliott. “The rude boy story was rarely shared in the same way that people would talk about punks, mods and skinheads. But it’s very clear that it influenced them. The truth of that story needs to be paramount. A cultural narrative is always integral or imperative to that.”

Return of the Rudeboy Series by Dean Chalkley x Harris Elliott

Return of the Rudeboy Series by Dean Chalkley x Harris Elliott

The Birth of the Dapper

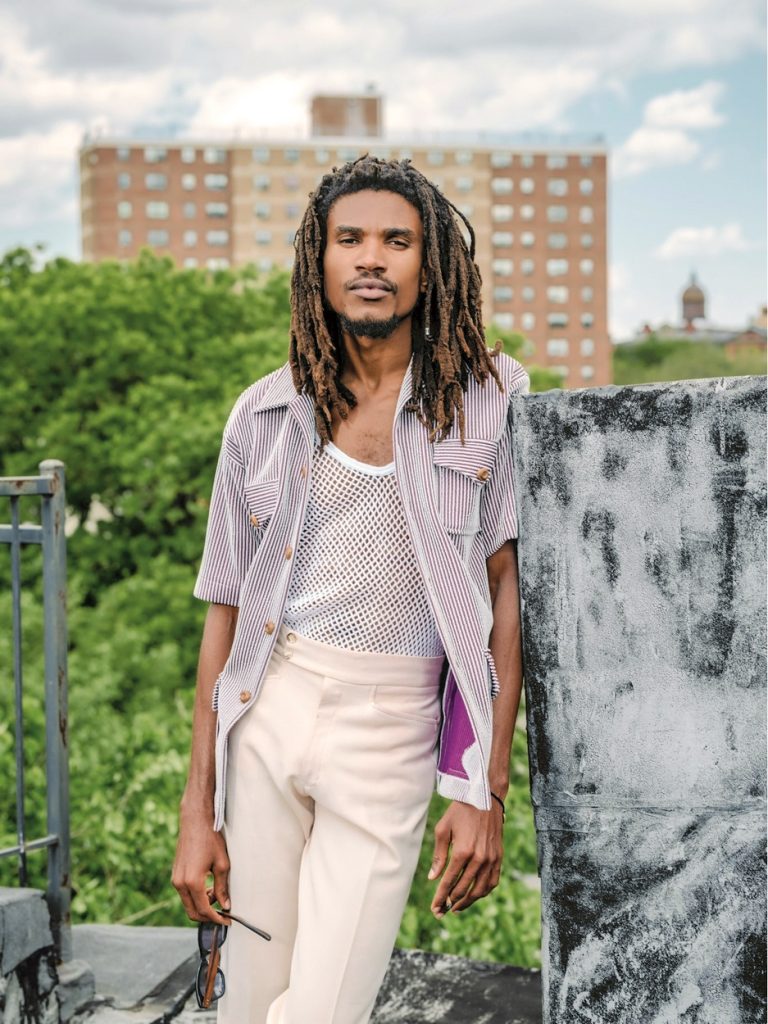

Photo courtesy of Wayne Lawrence

According to Elliott, the rude boy ethos fully blossomed as Jamaica gained independence in 1962. Its image marked a sociopolitical reckoning for Black youth facing poverty and high unemployment rates in the newly minted nation. For them, the style was anti-establishment, a fashionable resistance to the criminal labels society placed on them. The sleek tailoring clearly harkened back to respectable English suiting, accepted as the gentlemanly standard across the former British Empire.

But by twisting the proportions, and adding Caribbean flair in accessories and overall manner, the rude boy became a subversive persona with which Black youths could proclaim their self worth and value on their own terms. “There was a sense of self sufficiency outside of what the government and those with power deemed you can be in society,” says Elliott.

To this day, these harsh connotations associated with the rude boy endure as people may think of drugs and violence when they imagine him. Jamaican actor, musician, and dub poet Sheldon Shepherd thinks differently. Shepherd gained global recognition for his critically acclaimed role as gangster King Fox in the Idris Elba-directed film “Yardie,” based on the novel of the same name by Jamaican writer Victor Headley. Shepherd drew inspiration in part from the rude boy culture friends and family members displayed while he was growing up in Jamaica.

Sheldon Shepherd sees the rude boy persona as an escape from the real-life societal ills that people face, affecting more than any one individual reaches. “It originated among the downtrodden, among the people who were fielding for their identity, finding space in a world that they couldn’t really recognize and where they never really had a voice.” In Shepherd’s opinion, the rude boy is someone seeking power in a society where they feel powerless. “Power comes from going against the grain,” he says. “Being different, being outcasts of the system.”

He also argues that the rude boy’s rebellious heart has deep kinship with many of the cultural art forms that define Jamaica and the broader Caribbean. “Reggae music, dub poetry, dub music, dancehall, all express that rebelliousness,” says Shepherd. He, like others who are proponents of the culture, asserts that people often focus on the violent perception of the rude boy, instead of the systematic violence that created the conditions in which the archetype would thrive.

Revolutionary Tings

Shepherd, who is working on a dub poetry audiobook, sees a new generation of artists turning to rude boy style, reinterpreting its renegade legacy. We see this flame of rebelliousness in Grammy-nominated singer Koffee, who often opts for tailored suits and more gender neutral pieces at red carpet events, where many might expect her to wear a feminine dress. Her sleek outfits feel like a quiet dissent to the hyper-sexualization women artists often experience in the music industry. Inspired by rude boy style, Jamaican-British designer Bianca Saunders creates menswear that challenges the norms of gendered design, playing into the rude boy’s innate showmanship.

Photo courtesy of Leagh Heflin

A certified dancer, teacher and gender-neutral fashionista, Naala Nesbeth is part of this new wave pushing the boundaries of the rudie aesthetic. She sees herself following in the footsteps of artists like Pauline Black of music duo The Selecter, one of the most prominent rude girls of the late 1970s and early 80s, who challenged gender expectations.

A driving force in Nesbeth’s work is reimagining gender binaries in fashion, and by extension, the broader society. “In the Caribbean context, there needs to be more effort to educate people of difference. That’s why you have people like me that are here to start that conversation around sexuality and gender neutrality,” says Naala Nesbeth.

In particular, she resists the idea that this gender-bending fashion just means the exclusive adoption of male traits and clothing. “I’m not here to be a man, I’m not trying to take on a character,” she explains. “Fashion is masculine and feminine. I’m able to put those two elements together to create a balance. Why does masculinity have to be dominant, powerful, and femininity soft and light? It’s the power in each of them that I’m trying to put out there. This is me, how I am.”

Jamaican culture and Caribbean culture in general are ever evolving. But where does that leave the rude boy? Although the answer may change like the seasons of fashion, to quote Derrick Morgan on his eponymously titled track ― whatever it is “Rudies don’t fear.”