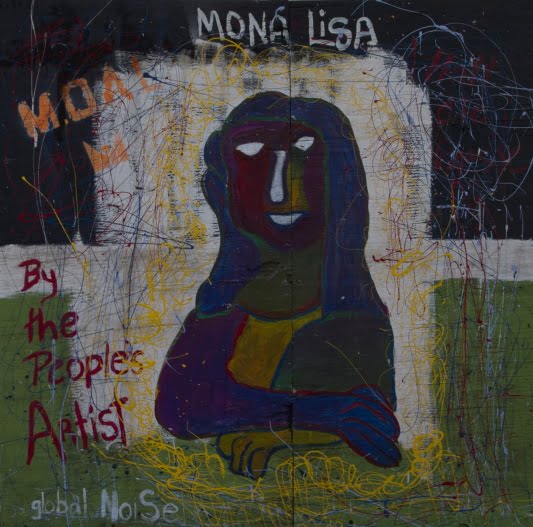

Stroll the streets of South Florida cities these days, and you’ll likely come upon odd-looking stickers affixed to utility poles, bus benches, and trees. The stickers bear the face of a gorilla, which is accompanied by the letters MOAL. But if you think the stickers were put up to announce, say, an upcoming circus, or the remake of a King Kong movie, you’d be mistaken.

So what’s up with the ubiquitous stickers?

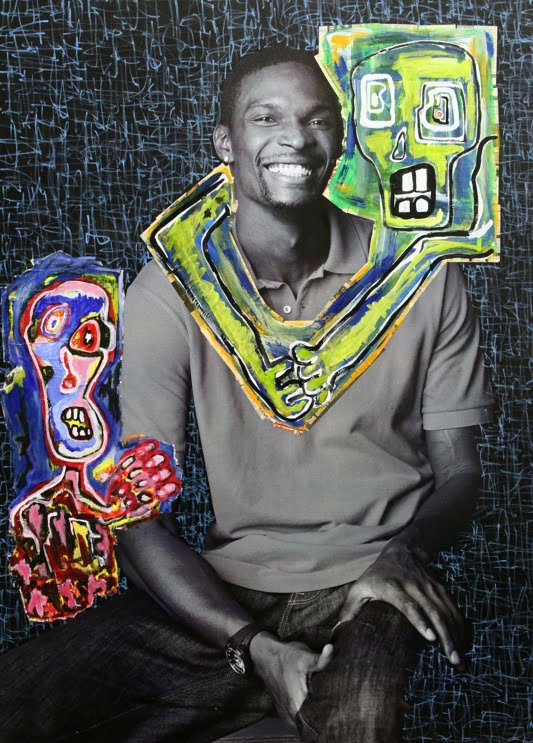

They’re actually the calling cards of Jamaican-born, self-described “raw artist” Elijah Mzilikaze. The gorilla face, coupled with MOAL (his nom de guerre, or alias, whose letters stand for “Mind of a Lunatic”) on the stickers, symbolize the transformation the artist underwent as a 19-year-old U.S. Army combat engineer participating in Operation Desert Storm (August 1990 – February 1991), the U.S.-led incursion into Iraq. “I experienced such savagery on the battlefield that it damaged my soul and my spirit.”

Because of his wartime experiences – which included the handling of mutilated bodies – Mzilikaze had difficulty readjusting to civilian life upon being discharged from the Army. He recalls: “My life took many turns – from good to bad, from strange to mystic. I had become half-man, half-ape.”

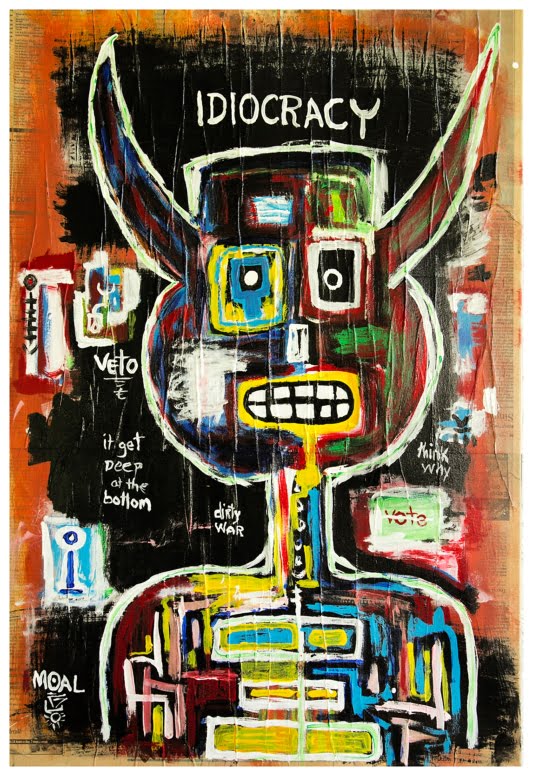

He soon turned to art as a way of dealing with the emotional turmoil. And although some of his pieces depict the horrors of warfare, others deal with less troubling subjects, often incorporating symbols from various continental and diasporic African cultures. A multi-media artist, Mzilikaze (pronounced zee-lee-KAH-zee) occasionally paints on canvas, but most often he paints on materials such as recycled wood, glass and plastic containers, household utensils, and items of furniture. On certain items he’ll sometimes attach miscellaneous objects to create assemblages.

At first glance, Mzilikaze’s art might invite comparison to that of other outsider artists, such as the late Purvis Young or Jean-Michel Basquiat. “I get it all the time,” he says. “Sometimes the comparison is to Purvis Young, but most of the time it’s to Basquiat. Basquiat was the first to appear on the outsider art scene, so now everyone, when they see a style that is kind of similar, they relate it to his style. But my approach to art is quite different.”

The seeds of Mzilikaze’s art career were sown during his childhood in Portland, Jamaica. “We didn’t have a lot of money, so most of our toys we had to make from scratch,” he recalls. “But when I got older, and started to explore the world, I stopped creating. Subconsciously, though, I was absorbing a lot of knowledge, so when it became time for me to get back into creating, it was easy to do. All I had to do was to draw on what I was doing as a child.”

Indeed, those creative seeds sown so long ago have borne fruit. Mzilikaze has lived in Miami since 1982. Over the years he has exhibited in a number of solo and group shows in the United States (New York, California, and elsewhere), Indonesia, South Korea, Japan, China, and France. He also has done considerable commissioned work locally, for clients ranging from the Museum of Contemporary Art in North Miami to the “Jazz Before Midnight” program on radio station WDNA (88.9 FM).

Striving for Higher Heights

The emergence of Miami and environs as an art mecca was aided in large part by Art Basel, which relocated from Basel, Switzerland, to Miami Beach in 2002. The event’s main activities take place in the Miami Beach Convention Center, but it offers opportunities for galleries in Miami’s Wynwood district and elsewhere in Miami-Dade County to showcase their collections.

So has Mzilikaze derived any benefit from the area’s newfound popularity as a destination for artists and art lovers?

“Very little,” he asserts. “Artists and collectors travel here from all over the world during the week of Art Basel. I’m right here, but I’m the invisible man. They see my work all year on Instagram – that’s where they contact you from – but when Art Basel comes to town it’s difficult to be part of things.”

He continues: “They go, ‘Oh, we love your work; it’s wonderful. Would you like to show at our establishment? We’ll send you an application.’ The thing, though, is that the application fee is $100 or $150. So you submit the application fee and photos of your work, and they approve it. Then they say, ‘Okay, you’re approved to show at our gallery. Here’s a five-by-five foot wall: $1,500.’ The kicker is that they’re charging people to come into their establishments to see their collections; so, even though you get to keep the proceeds from sales (if any), you’re actually paying the gallery owners to be part of their exhibitions.”

As Mzilikaze sees it, the deck is stacked against most local artists, and especially minority artists. “The biggest challenge for minority artists in South Florida is having places to show their work, and to have people who understand the work that they’re showing. Or, if they don’t understand, to at least try to educate the public about the work.

“Now there are platforms that call for artists, but there always seem to be hidden agendas,” Mzilikaze says. “Decision makers might not like you as a person; they might not like your work; and your work might not be the kind of work that they’re looking for. So you’re back to square one. You need people who understand you, and who live in your community, and who can identify with you. If someone can’t identify with you, then they’re not likely to care about showing your work.’

He offers as an example works that address societal problems: “Let’s say that I have a painting about police brutality toward black people. Most establishments are Caucasian-owned, so they’ll have no interest in showing your work. That’s the reality. But an artist lives in, and is part of, a community; his or her role, then, is to point out what’s affecting the community, to acknowledge what’s going on in the community.”

And how does Mzilikaze spend his time when not making art?

“Typically, I’m making art 24 hours a day,” he says. “Even if I’m not physically creating something, I’m reading, or I’m researching how to make something. I’m constantly educating myself.”

Another of his activities is gardening, and he spends considerable time tending to the assorted vegetables and tropical trees (soursop, sweetsop, ackee, etc.) growing in the front and back yards of his northwest Miami-Dade County home. “Gardening, like art, is therapeutic,” he says. “I use them to help me cope with the demons which are constantly at war in my head – demons caused by what I call the alphabetical disorders I have: PTSD [Post Traumatic Stress Disorder] and ADD [Attention Deficit Disorder].”

Not surprisingly, coming as he does from a rural area of Jamaica, Mzilikaze is adept at coaxing the earth to offer up her bounty. In fact, if he weren’t making art, he very well could find success as a farmer – something he has considered pursuing on land he owns in Portland. But does that mean he’d give up his art for a farming career?

“No way!” he insists. “These are the two loves of my life, and I love them equally, so I’d just have to figure out a way to devote equal time to both.”

Learn more about the artist at his Instagram @MOALart and Facebook