Taking the baton, a new generation is building on the legacy of Black Caribbean activism in the United States.

There are always certain galvanizing points in history ― cataclysmic moments that forever separate the time before from the time after. For many in 2020, the murder of George Floyd at the hands of police was one such pivotal moment in time. The event sparked an unprecedented social reckoning with racial inequity. And for many contemporary Caribbean-American activists, the moment also prompted them to examine their own role in the pursuit of justice for the Black community in America.

Black Caribbean leaders have long been an intrinsic part of the struggle for Black empowerment and liberation in this country. Figures like Trinidad-born Black Power leader Kwame Ture, Caribbean-American politician Shirley Chisholm, and Jamaican political activist Marcus Garvey were at the forefront of the fight for racial justice in this country.

Following their example, how is the next generation of Black Caribbean American activism responding to the same unresolved issues? And how are they carrying the emotional burden of this responsibility? Exploring the way forward, we spoke to Caribbean-American activists as they reflected on this moment, how they face challenges similar to those of their forebears and how they chose to respond to their legacy.

Rickford Burke

Rickford Burke is no stranger to protesting for a worthy cause. As a prominent community activist, law consultant and president of the Caribbean Guyana Institute For Democracy (CGID), the Guyanese native has long advocated for the improvement of key issues affecting the Caribbean-American community in New York, including gentrification and police brutality.

Yet, in the aftermath of George Floyd’s murder, Burke wondered whether he too should march in the streets for justice. “I knew that we had to do something, but I was a bit skeptical because it was in the middle of the pandemic,” he explained. Something clicked for him while watching footage of the protest in Minnesota. “I saw a Jamaican flag. I said ‘Wow, they have Caribbean Americans all the way out there on the front lines fighting for justice.’ New York City is the capital of the Caribbean immigrant population in the United States. We have to show up too.”

Thus was born the Caribbean Americans For Justice march, held last June in Brooklyn. Organized by CGID in collaboration with other local advocacy groups, the rally provided a way for the Caribbean-American community in New York to declare solidarity with racial justice protests held around the world.

The event struck a chord, as Burke reported that staging had thousands in attendance and received nationwide coverage. But beyond the placards and newsreels, Burke knows the fight for lasting change happens away from the camera. The march sought to pressure local policymakers “to guarantee police accountability, justice for victims of police brutality and other abuses, as well as reverse inequities that plague African Americans and other minorities,” Burke explains.

Though the rally is gone, the CGID continues its efforts, hosting community seminars and other events meant to raise awareness about police violence and other related concerns. Through these events, they remain committed “to teaching young people the law, and how to react to police abuses,” said Burke.

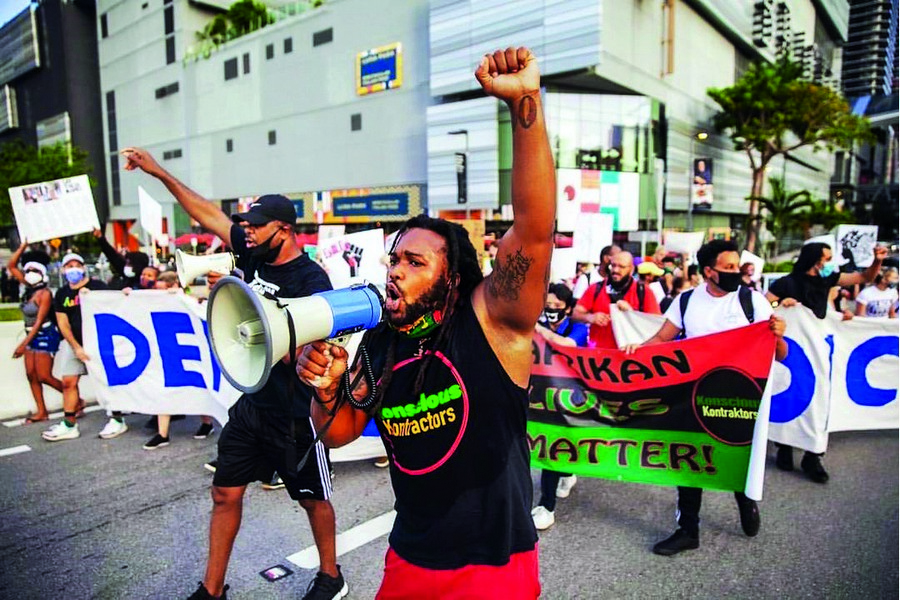

François Alexandre

Ayisyen-American (Haitian-American) François Alexandre knows firsthand the brutality of police violence against the Black community following one horrific night in Miami. In 2013, he was heading home, celebrating along the way with the joyful crowd that gathered on the streets after the Miami Heat won the NBA championship. But chaos ensued when police started pushing people, slamming Alexandre to the ground. Five officers piled on top of him, beating him and breaking his eye socket.

The surveillance video of his assault, like so many other such encounters, has reemerged online following the murder of George Floyd. Seeing the renewed urgency his case and others have received feels both bittersweet and necessary for Alexandre. “George Floyd shouldn’t have had to die for us to make a change,” he said. “But he brought light to my story. He helped me heal.”

This experience has only strengthened his resolve in activism. For him, the heart of many of these issues, including police brutality, lies in Black communities not feeling secure in their own neighborhoods. These areas are often over-policed instead of receiving civic investment ― only getting attention when they are being gentrified by other wealthier groups.

This push for civic investment is the driving force behind his organization, Konscious Kontractors, which provides landscaping and renovation services for local Black communities. He first started the group in 2017 following Hurricane Irma, helping neighborhoods that weren’t receiving enough resources for post-storm recovery. But the group continued their work “out of a necessity to fight climate gentrification, to bring beautification, and bring consciousness to the community,” Alexandre explained. Through this work, he has also been involved in organizing street cleanings, food drives, the construction of community gardens, art initiatives and many other projects aimed at uplifting his community. He hopes to continue this work as a candidate for Commissioner District 5 with the City of Miami. It’s an area with a large Black Caribbean population, especially those from his native Ayiti.

Like his predecessors, Alexandre sees justice for the Black community as a legacy issue ― one that must be carried through generations. “The future belongs to the children, and the children will be solving a lot of the problems that we face now, problems that we’ve made for them.” But, Alexandre hopes, “if I lay the first brick, someone will lay the next one.”

Equality for Flatbush

Long a Black Caribbean enclave, the Brooklyn neighborhood of Flatbush in New York has seen its share of police harassment. But for founder of Equality for Flatbush, Imani Henry, poor policing is just a symptom of a bigger problem. Beginning in 2013 as a Black Lives Matter group, the organization “focused on tenant harassment and police violence happening in the Flatbush community,” Henry explains. “[But] we really saw and put together the connection with gentrification, displacement, and police violence and how the police are used against our communities Brooklyn-wide.”

Since its inception, the organization has broadened its campaign, tackling police accountability, affordable housing and gentrification. Their work has grown to have an impact on the larger Brooklyn community, expanding outside of Flatbush. The group’s base is also majority Black Caribbean women migrants.

For Henry, a 30-year veteran in grassroots campaigning, Equality for Flatbush became a powerful way to channel his own frustrations about gentrification and displacement in Brooklyn. “As an activist, I can be angry, and hurt, and feel all kinds of ways about these places changing, or I can do something about it,” he said.

In the aftermath of George Floyd’s death, the organization also provided a younger generation with meaningful ways to bring purpose to their heartbreak by engaging in community activism. This proved true for Equality for Flatbush’s director of administration, Kasslyn Pompey. Like many of her peers, she was jolted into action following the events of 2020. “We haven’t really progressed as we would have imagined,” says Pompey. “Although there are steps and strides, there is still so much to be done for us to come to a place of tranquility as Caribbean people and Black people.”

While Pompey speaks, Elgin Elias nods her head in agreement. As a homeowner leader at Equality for Flatbush and longtime resident of Bedford-Stuyvesant, she has seen firsthand the slow and limited progress. She herself experienced its effects when her building was damaged due to poor construction practices at a neighboring site during a gentrification project. Despite the difficulty, age and wisdom give her faith in continuing the struggle. “We [Caribbean Americans] have to be united,” she urges. “Until then, we will not make any strides. I long to see the day where we can see that.”