In his 1995 autobiography, “My American Journey,” Colin Powell recalls a near-death experience in Jamaica during his visit there three years earlier while representing the United States as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Flying in a Jamaica Defence Force helicopter, Powell heard a sudden, sharp crack. The helicopter’s transmission had seized. As a former soldier who had survived a helicopter crash during his tour in Vietnam, he knew well what would happen if the aircraft that carried him and his wife Alma failed ― plummeting them into the azure waters of the Caribbean Sea below.

Reflecting later on their swift rescue by Jamaican pilots, Powell could not help but marvel at the irony of the moment. “What had been the land of my folks’ birth,” he wrote, “had nearly become the site of their son’s death.”

Powell was thousands of miles away from Jamaica when he passed away from COVID-19 complications on October 18, 2021, at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center. Yet the land of his family’s birth shaped so much of the man he became: the four-star general who made history as the first Black national security advisor, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and secretary of state. As an unyielding public servant dedicated to fortifying a more perfect union, he will forever be remembered not only as a great American but also as an embodiment of the Caribbean-American ideal.

An American Dream in the South Bronx

So much of Colin Powell’s journey represents the hopes of American immigrants for their children. Perhaps Jamaican immigrants Luther and Maud Ariel Powell had lofty wishes for their son when he was born on April 5, 1937, in Harlem, New York. They were among the earliest waves of West Indian migrants ― the proverbial “tired and poor, those huddled masses” that came to this country in search of a better life. But the America Powell met at his birth was in turmoil. The country was still recovering from the Great Depression, and would soon be plunged into the fog of World War II.

Yet in his memoir, Powell remembers his early years living in the South Bronx defined not by darkness, but by light ― bathed in the warmth of his close-knit West Indian community. In true Caribbean fashion, Powell recalls being simultaneously scolded and fussed over by matriarchs “who set the standards, whipped the kids into shape, and pushed them ahead.” He remembers watching his father, a shipping clerk who first came to America on a banana boat, toil “to become something more than he had been, and to give his children a better start than he had known.” These experiences, both mundane and extraordinary, taught him that success came only through hard work and personal sacrifice.

“Education, personal achievement, respect, [and a] God fearing” nature were vitally pressed in Powell’s home, says Jamaican-born scholar Dr. Basil Bryan, who grew acquainted with Powell while serving as Jamaica’s consul general in New York and deputy ambassador in Washington D.C. The enduring lessons learned from this West Indian community helped Powell forge his own work ethic and moral compass, which the U.S. military would put to the test.

The Birth of a Leader

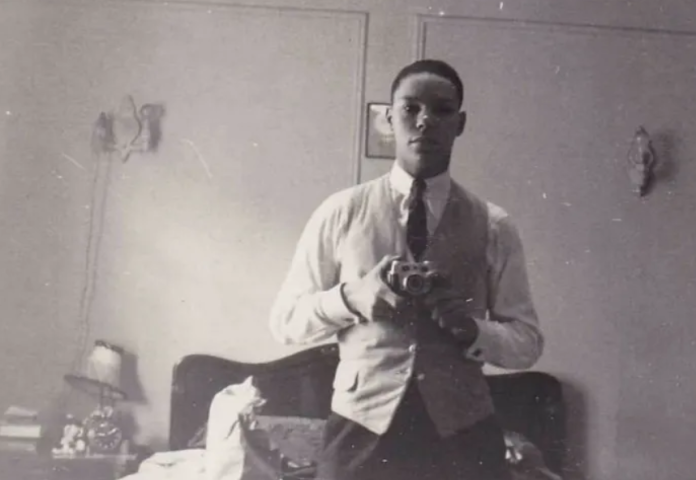

In his memoir, Powell remembers feeling transformed when he first donned the simple olive-and-brown uniform of City College’s Reserve Officers’ Training Corps. Back then, his uniform was bare and unadorned, devoid of the insignia which would later symbolize his distinguished career.

The military has long given first-generation Americans a way to claim their nationhood, display their patriotism and find rare opportunities for advancement. This proved true for Powell, even when forced to swallow the bitter medicine of playing “the good Negro” in the newly desegregated U.S. military. Powell managed to find a sense of belonging within the institution and cleaved to its structure and discipline while serving two tours in the Vietnam War.

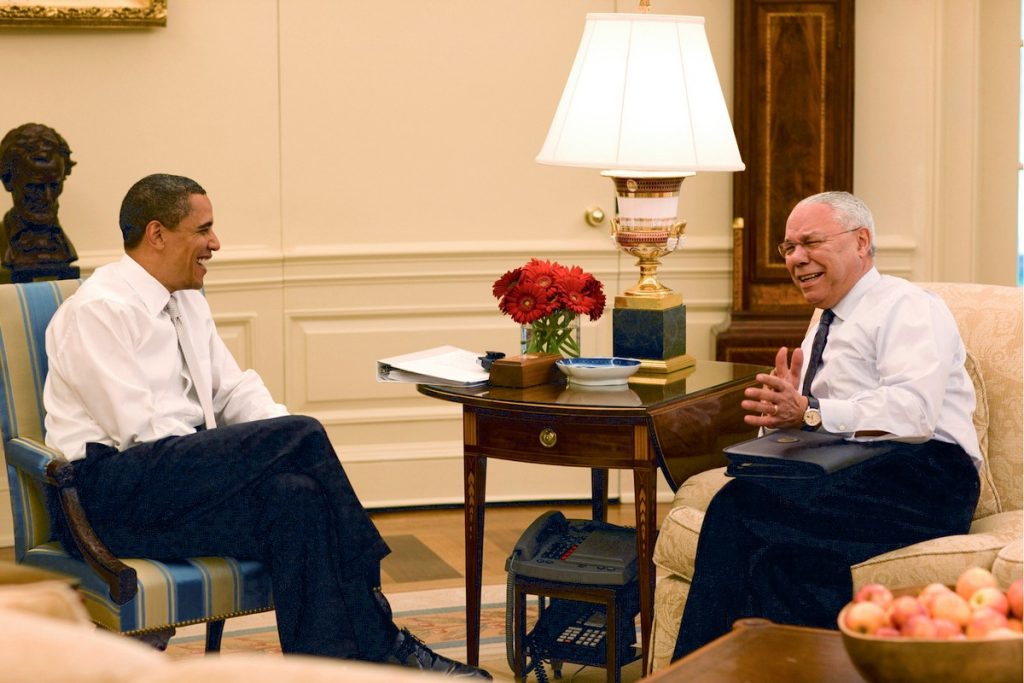

Colin Powell with Ambassador Sue M. Cobb. (Courtesy of Cobb Family Foundation Inc.)

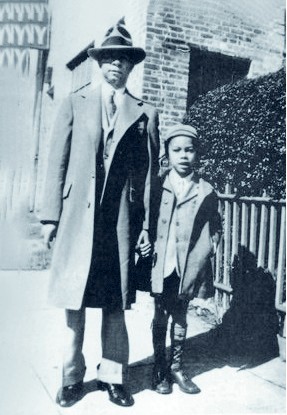

A young Colin Powell with his Jamaican father,

Luther, in New York. (Courtesy Colin Powell)

His star would rise quickly as a leader in the military and later at the State Department. Sue M. Cobb, former U.S. ambassador to Jamaica during the George W. Bush administration, notes that Powell was “one of the kindest, most thoughtful, careful, and loyal leaders and friends” she had ever known. Pamela E. Bridgewater, former U.S. ambassador to Jamaica during the Barack Obama administration, shares this sentiment. “He wanted people to be the very best that they could be,” says Bridgewater. And though he “demand[ed] excellence, he helped others reach that level if they hadn’t gotten it.”

Bridgewater continues to hold dear a Powell mantra: “take care of the troops and the troops will take care of you.” This human-centric approach to military leadership provided the foundation for what would become known as the Powell Doctrine: a set of criteria dictating the use of force abroad, predicated on the protection of U.S. strategic interests, a clear plan for winning, a set exit strategy and wide public support. In summary, war should be decisive, but only as the last resort. These principles helped him guide America through the 1991 Gulf War ― a conflict defined by calculated military intervention and international support.

Litmus Test

Powell’s record made him a rare breed among an increasingly partisan nation. Serving both Republican and Democratic presidents, he became a Washington figure respected by politicians on both sides of a thorny aisle. Still, any honest interrogation of Colin Powell’s life must contend with a singular, uncomfortable truth: Powell may have been a high-ranking military and political leader, but he could not overcome America’s imperialistic ambitions. In the name of this country, he ultimately played a part in decimating the lives of many peoples of color abroad.

Powell sits with Ronald Reagan circa 1980s. [Public Domain]

A young Colin Powell meets with Richard Nixon. [Public Domain]

Powell was accused of whitewashing his 1968 investigations into the Mỹ Lai massacre of unarmed South Vietnamese civilians by U.S. troops. And in 1989, during the U.S. invasion of Panama to overthrow dictator and former CIA ally Manuel Noriega, Powell, as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, oversaw the bombing of impoverished communities like Panama City’s El Chorrillo, a neighborhood first populated by Caribbean migrants who came to work on the Panama Canal. One of Powell’s most enduring legacies will be his role in the Iraq War while serving as secretary of state. History will remember how he contradicted his own doctrine when he advocated for invasion before the United Nations Security Council in 2003.

The America he represented that year, however, differed dramatically from the nation that launched the measured military operations of the 1991 Gulf War. This was America post-9/11 — scared and fearful of unseen enemies seemingly emerging everywhere. Internally, Powell’s advocacy for a more calculated response could not deter a presidency primed for war. Instead, taking advantage of Powell’s staunch reputation, the administration intentionally selected him to sell the Iraq War to the world, using erroneous evidence that ignored marked objections among America’s own intelligence community. He would later describe that event as one of his most momentous failures.

Through it all, Powell’s ethos, successes and defeats serve as inspiration for the next generation of Caribbean-American leaders. These future luminaries must confront systemic racism, climate change and gender inequality. To their great benefit, they will have the indomitable legacy that Powell left behind, proof that people of West Indian descent belong comfortably among the leadership of the highest offices on the world stage.

Powell invested his hopes into this next generation when he founded the Colin Powell School for Civic and Global Leadership at his alma mater, City College of New York (CCNY). The nonpartisan institute is dedicated to nurturing more minority voices in shaping American policy ― ensuring the future of the nation need not depend on one great man. It will be left in the hands of prepared and capable people.