If you’ve read Staceyann Chin’s 2009 coming-of-age memoir, “The Other Side of Paradise,” you know that even as a little girl in rural Jamaica, she was outspoken. As her older brother described her in the book, she was always the child who wanted to talk “‘bout things what nobody else want talk ‘bout.”

Some things never change. In her years as a critically-acclaimed poet, playwright, performer and activist, Chin has been an unyielding advocate for the marginalized while challenging the powers that be. No status quo is safe. She moved from dismantling social hypocrisies with her thunderous performances on the iconic HBO TV show “Def Poetry Jam” to capturing her convention-breaking journey to motherhood in her 2015 one-woman play “MotherStruck!”

For me, perhaps her greatest impact lies in her work giving unprecedented LGBTQ+ visibility to the Caribbean diaspora. She was the first Caribbean queer activist and public figure I knew that so openly spoke to our experiences. For more than 10 years, I quietly came out to close friends and family, then finally came out publicly in 2013. I decided then to write a memoir sharing my own story.

Discovering Chin’s book empowered me to begin. Her frankness connects with me profoundly as a Jamaican who grew up in a culture that has shunned queer Caribbeans. There was and often continues to be blatant hostility spewing from speakers at Saturday night dances, and fire and brimstone at Sunday morning church service.

Room to Speak

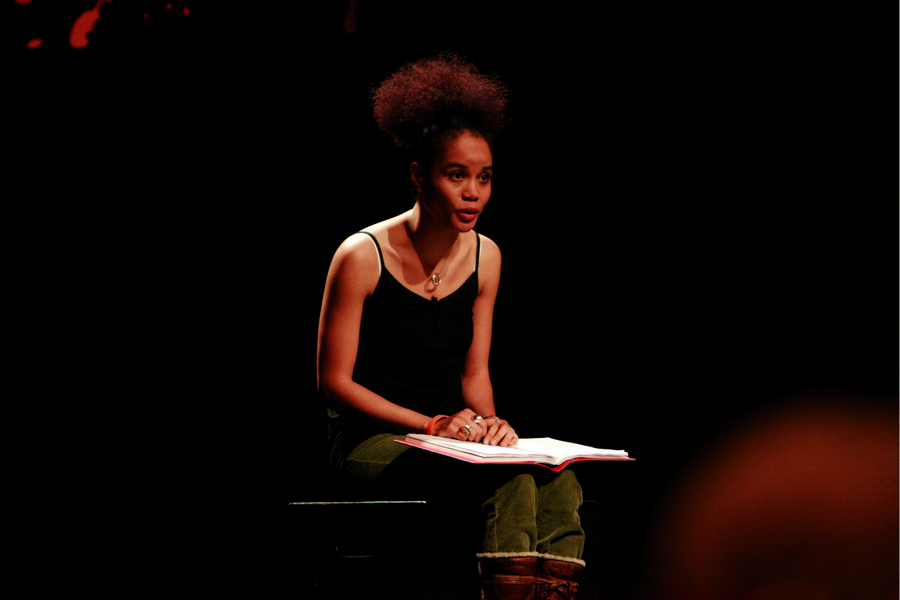

For Chin, speaking out has never been a question of bravery, but one of sheer survival ― a way of reclaiming herself in the aftermath of an earth-shattering moment in her life. While she was a student at the University of the West Indies, Mona, she was sexually assaulted by a group of men who attacked her for daring to confidently and openly exist as the gay woman she is. Simply living on the island was a risk. In the relative safety of New York — a strange city in a strange country — performing her unedited, unfiltered poetry and sharing her truth on stage felt freeing.

It was so important to me to have room to speak, to feel as if my story could be told and heard.

“It was so important to me to have room to speak, to feel as if my story could be told and heard,” she shares with me in an interview, recalling her development as an artist in those early days. “I started to tell the story to whoever would listen, the small cafes in Brooklyn and confessional groups with other Black lesbians.”

These first forays soon led her to bigger national stages — from the “Def Poetry Jam” TV and Broadway shows to her landmark interview on “The Oprah Winfrey Show” in 2007. “I was at the right place at the right time, with the right identity marker,” says the author. “I was interesting and new enough for the powers that be to take notice of me.”

The American Dream-come-true narrative could have easily overshadowed the subtle complexities of her story. But while the Big Apple provided her refuge in one way, she quickly realized that New York was no paradise. In the city, “it was good to be a gay woman, but I found that it was increasingly difficult to be Black,” she explains.

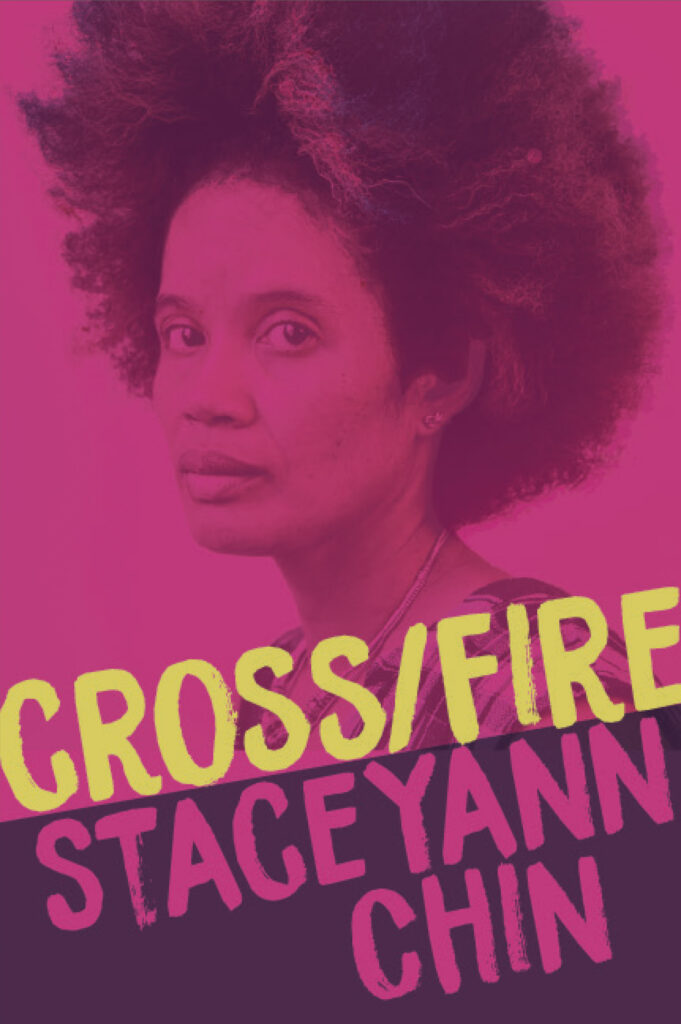

In response to the reality of living in America, her work has confronted racism, economic inequity and other injustices holistically. The result is always raw and vulnerable. In her book of poetry “Crossfire: A Litany for Survival,” published in 2019, we experience the depth and breadth of her passions, exploring love, sexuality, politics, feminism, family, domestic violence, international human rights and other topics at the intersection of her experience as a lesbian, immigrant, single mother and Black woman.

From One Generation to the Next

Her advocacy and art have only intensified since becoming a mother. Her 9-year-old daughter, Zuri, is already enthusiastically engaged in her mother’s activism. You can watch her blossoming as a thoughtful speaker on Chin’s inspiring YouTube series “Living Room Protest.” Alongside banter about street safety and back-to-school worries, mother and daughter have created their own safe corner of the web to passionately discuss social issues, including body positivity, gun control and rights for migrant families.

Though becoming a mother has only made the urgency of her causes more acute, Chin knows real change is a long game. “It might be slower than we would like,” she says, “but those of us who do the work know that the work is for your life and for your children’s lives, and for your children’s children’s lives.”

For her next book project, she’s interested in exploring her relationship with her mother, who was estranged during her childhood ― a journey captured in a documentary in development called “Away With Words,” to be directed by Jamaican-Canadian filmmaker Laurie Townshend.

For now, her journey has taken her back to Jamaica. In the heart of the pandemic, Chin left New York with Zuri to visit the island for just a few weeks. Months later, she’s still there and has no idea when she’s leaving.

Connections at the Heart

The Jamaica she left all those years ago has changed in many ways, thanks to the hard work of local activists and organizations like the Jamaica Forum for Lesbians, All-Sexuals and Gays (J-FLAG). On the world stage, Jamaican contemporary literature is also prominently represented by other LGBTQ+ authors like Nicole Dennis-Benn, Marlon James and Kei Miller.

As far as overall attitudes, “they have definitely shifted in the middle class,” says Chin. “But we have to recognize that such privilege begets safety.” As a child of humble beginnings, she says, “I’m very aware that poor people are unsafe.” So she focuses her advocacy far beyond LGBTQ+ issues. She fights for all who need the fight. “So it’s not just poor, gay people [who] are unsafe. Poor, straight people are unsafe. Poor girls are unsafe. Poor, Black men too are unsafe from the police here.”

The unsafe are the people who drive the creativity at the core of her art. One of her greatest badges of honor, she says, “is that my books are the most stolen in Barnes and Nobles in New York City.” She supposes the people who steal them are very much like the young woman she was when she first came to America — struggling to get by, trying to find a safe place in a system “that doesn’t speak for them or take them into consideration.”

She hopes that she has provided a safe harbor in her book and that those who need to see their experiences reflected back in the stories they read, wherever they are, will always find a home among her words.