Cristiano Berti’s new book, Boggiano Heirs, tells the stories of the Boggianos, a group of enslaved people owned by Antonio Boggiano, a wealthy Italian merchant residing in Cuba in the early 19th century, whose surname was imposed upon many enslaved people, and transmitted to their descendants up to this day.

In the early 19th century, slavery was widespread in Cuba. Racism was also a rampant issue as the Cuban society was divided into classifications according to one’s proximity to whiteness, defining a woman of mixed African and European descent as a mulata, of mixed Indigenous American and European descent as a mestiza, of mixed white and mulata descent as a tercerona, a descendent of mixed white and tercerona descent a cuarterona, and so on in the numerous possible combinations.

By the time Antonio Boggiano arrived in Cuba, it was fairly easy for him to amass enough money to purchase a coffee plantation near the city of Trinidad – in an area named San José de los Puriales – along with slaves who were forced to exert labor to cultivate it.

The enslaved people endured poor living conditions and harsh treatment, particularly those who worked in sugar plantations. Poor sanitary conditions, scarcity of medicines and overcrowding made the enslaved people more vulnerable to epidemics. Due to the hardships the enslaved faced, their lifespan was cut short – those in sugar plantations had a lifespan that averaged around ten years, while those in coffee plantations had a comparatively higher lifespan.

Those who attempted to flee, known as cimarrones, were often captured and returned to slavery after being subjected to terrible punishments. According to customary law, the only reliable way to freedom was through its purchase. As few had the means to do so, many had their fates sealed as slaves. Fortunately, some of Boggiano’s slaves did precisely this: They bought their own freedom.

While the Cuban Boggianos of this era carry Antonio Boggiano’s surname, they do not directly descend from his lineage. Instead, the book explores other possibilities, such as the customary practices in Spanish colonies that baptized enslaved people under the surname of their enslaver.

Today, the only tangible relic of Antonio Boggiano’s many businesses and properties is a white marble altar found in the Santísima Trinidad’s Church. However, the author emphasizes that the marble altar is not particularly interesting compared to the immaterial legacy constituted by the transmission of his surname that can be found among many Afro-Cubans to this day.

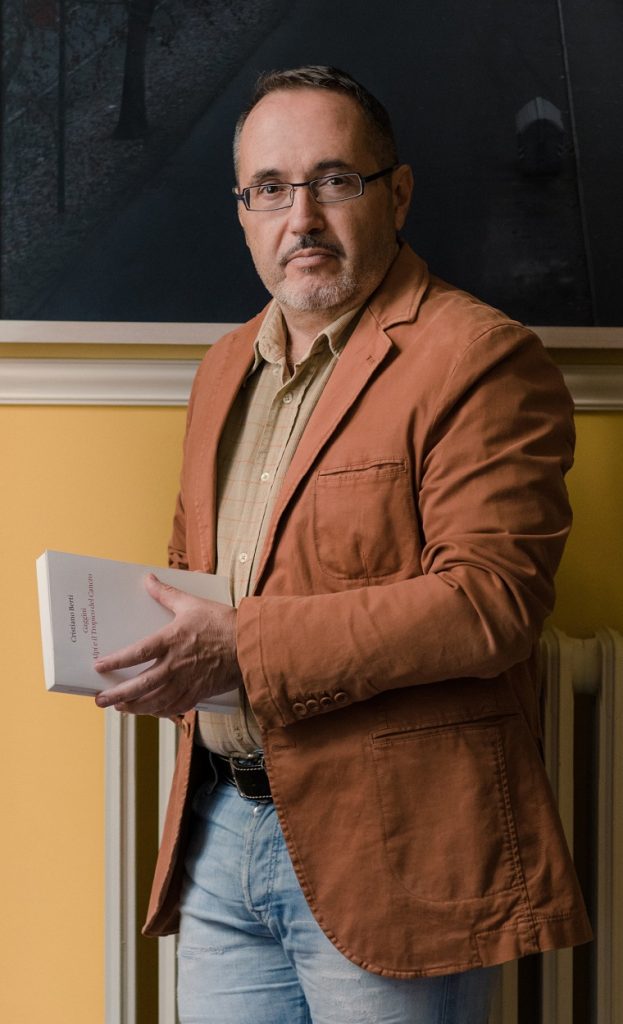

The result of five years of research, Cristiano Berti’s Boggiano Heirs is primarily an artist’s book but takes the form of a historical essay. His recent projects involve the publication of an artist’s book, along with works created using the typical mediums of contemporary art. The first of these volumes was published by Quodlibet in 2017, and it is entitled Gaggini. Le Alpi e il Tropico del Cancro.

The book closes with a conversation with American art critic and author Seph Rodney on art and the representation and memory of slavery:

“You turned toward the mystery of the Boggianos to see what they could tell you about the wider developments within the Caribbean. I think it’s valuable that you have uncovered a hushed history of entrepreneurship, travel, exploitation, enslavement, aspiration, intermixing of cultures and ethnicities, and laborious self-possession.”

Boggiano Heirs is distributed in the US by IDEA Books and produced thanks to the support of the Italian Council’s program for the international promotion of Italian art, under the General Directorate for Contemporary Creativity of the Ministry of Culture.