“God himself says that you have to forgive to be forgiven. I don’t forget what happened. But I do forgive.”

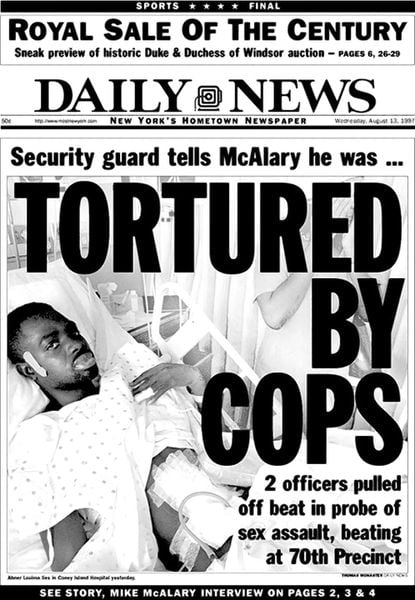

A soft-spoken Haitian immigrant living in New York, Abner Louima was just 30 years old when, on August 9, 1997, police officer Justin Volpe falsely accused him of assault outside a nightclub.

At the 70th precinct station in Brooklyn, Volpe and his fellow officers inflicted an hours-long attack on Abner Louima in one of the most shocking documented cases of police brutality in U.S. history. Louima sustained life-threatening internal, external and psychological injuries. Now, after 23 years, he credits faith, family, and the resilient spirit of Haiti and the Caribbean for making it this far.

“We are survivors. We can overcome any adversity,” he said.

His is a tale as old as time for African Americans. But for newer immigrants in the African diaspora, inherent targeting of Black people at the hands of rogue police officers is a newly familiar phenomenon. This diaspora, having left their homelands in search of the great American Dream, has come to learn that too often Black families in the United States are left mourning the death of targeted loved ones and wondering whether justice will ever be served. Louima recognizes that he’s one of only a few.

“I’m thankful because God wants me alive to speak about my own story. Most of the people that have been victimized really don’t have a chance to speak,” he said. Acknowledging his higher calling, he grants, “If God saved my life, he saved it for a reason.”

In a rare occurrence, Abner Louima’s perpetrators were tried and convicted. In a separate civil case, he was awarded the largest settlement in a police brutality case in New York City’s history — $8.7 million. His abusers were jailed; Volpe is still serving time in a 30-year sentence.

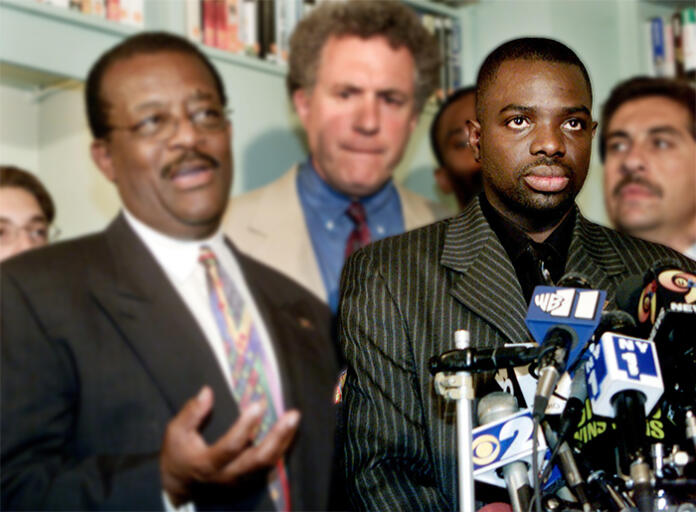

At the time of Volpe’s conviction, Louima became the icon of a movement. Black leaders, like Al Sharpton and Johnny Cochran, and advocates from around the world, rallied around him. An international campaign arose, much like the groundswell that followed the recent murder of George Floyd. Yet even now, a solution remains out of reach.

“I didn’t think that I would be talking about [police brutality] 20 years later, but it seems like nothing will change,” Louima said.

Though faith and family have been his support, dealing with the trauma is an ongoing battle.

“Each time there’s a case of police brutality or police misconduct, it brings back all the memories,” he said. But, “you have two choices. Either you let it affect you, or you deal with it. I have no choice but to deal with it.”

Today, living in South Florida, Louima is a real estate developer and philanthropist. Connecting with fellow survivors has become a central part of his healing process. He finds comfort offering them guidance and support as well as advocating for legal reform to deter future police abuse.

In the immediate aftermath of his own ordeal, Louima said the support of the community, particularly from the Haitian diaspora, “gave me courage.” Still, as long as the problem persists, so will he.

“We have to keep fighting until we get systemic change,” he said. “They are not going to hand it to us. So we have to keep fighting.”