In the months between Miami Carnival in October and the New Year, South Florida is usually busy with a slate of music concert, food festival and holiday gatherings. This time is filled the silky melodies of steel pan and calypso, parades in the streets and a waft of exotic spices from foods fresh off the grill. But not this year.

COVID-19 silenced the spirited gatherings that anchor Florida’s West Indian-themed calendar. The pandemic has been devastating to Caribbean-American communities, including businesses and families. In addition to navigating the dual financial and health crises, some island immigrants have battled to maintain their legal status—even as they worked essential jobs that kept health services and critical industries running.

A Grinding Halt

When refrigerated trucks (mobile morgues) in New York City became a horrific icon of the world’s COVID-19 hot spot experience, business people took heart. By March, Eddy Edwards knew things were changing. As founder of the popular Grace Jamaican Jerk Festival held in New York City and Miramar, Florida, he saw the writing on the wall early.

Edwards decided the risk of the event in Florida wasn’t worth it, even with social distancing. “I didn’t want to be that guy,” he said of his fear that an in-person festival could become a super-spreader where the virus is passed to many people in one area.

The celebration was among many felled in Florida by the pandemic, from Afro-Carib Fest to Haitian Flag Day. The quiet festival season soon became yet another symptom of the outbreak that shredded the core of the Caribbean-American community—disturbing all work, school and play.

Its most heartbreaking metric is the death toll. Current reports on deaths and hospitalizations from COVID-19 do not specify the impact on Caribbean communities since data lump together many people of African descent. What is known is that COVID-19 has ravaged the Black population in Broward County, Florida. According to reports through November 2020 from Florida’s Department of Health, Black people accounted for 25% of positive cases. Of those who got sick, about 40% were hospitalized and 36% died. These numbers were markedly higher than statewide percentages where the Black community made up 15% of infections, 23% of hospitalizations and 19% of deaths.

Gail-Ann Brown and her family are among so many others in the community whose lives have been disrupted by the virus. This summer’s losses range from the pedestrian to the tragic—from a canceled trip back home to Jamaica, to being unable to attend her aunt’s funeral in England, forced to watch from afar via Zoom.

Dr. Michelle Powell observed that this prolonged separation from loved ones has mental health consequences. Among patients at her North Miami Beach practice Powell Health Solutions (25% of whom are of Caribbean descent), she’s seen an increase in COVID-related stress symptoms. These include insomnia, random uncontrolled feelings, anxiety and crying spells.

In contrast to more chronic conditions, Dr. Powell attributes these to situational depression which occurs following experiences of loss or major life changes. Some people have experienced “real, tangible things” such as pay cuts or strains on reliable housing.

“The most important thing for people who are experiencing [symptoms] to know is that it doesn’t mean you are weak,” says Powell. “When the pandemic is managed, we will see people developing coping skills.”

The Cost of COVID

Mandatory isolation has an economic toll too. Many businesses have been affected by social distancing protocols, especially in the hospitality industry. This disproportionately affected local Caribbean-American workers, says Andy Ingraham, president and CEO of the National Association of Black Hotel Owners, Operators and Developers (NABHOOD). “About 50% of the people in the hospitality industry in South Florida have ties to the Caribbean, [including] longshoremen, purveyors and travel agents, ” he said. “And we found that 90% of the people laid off at the start of COVID were people of color.”

“They have been hit very hard,” said Jamaican-born Broward County Commissioner Dale Holness. Eying the recovery, the county is helping businesses stay open or reopen with support from the CARES Act federal stimulus funds. Meanwhile, Holness also predicts many residents soon will need help to keep a roof over their heads.

“A large percentage of residents have been devastated. They have no money to pay bills and no ability to pay their mortgage or rent,” Holness said. To combat the impending homelessness crisis, the county spent $17 million of its $25 million of CARES Act funds for housing to assist people living in zip codes with high poverty rates.

“Most poor people have suffered more than the people who are wealthy,” Holness said. “So we prioritized. We used targeted databases, robo calls, texting and email blasts. [We] notified cities that have residents who meet the area median household income [requirements] about the available funds. We have funding for those who need housing to isolate themselves. And we have given money to not-for-profits like the Urban League of Broward County.”

Left Behind

Despite these COVID-19 programs supporting residents, Marleine Bastien, executive director of Family Action Network Movement, believes many of her clients in the Caribbean community have fallen through the cracks.

Many of the vulnerable are undocumented immigrants. Others are among the nearly 18,000 with Temporary Protected Status (TPS) who are classified as essential workers in Florida, according to the Center for American Progress. This includes many Haitian immigrants, who were granted TPS approval following the devastating 2010 earthquake that killed an estimated quarter million people in their nation.

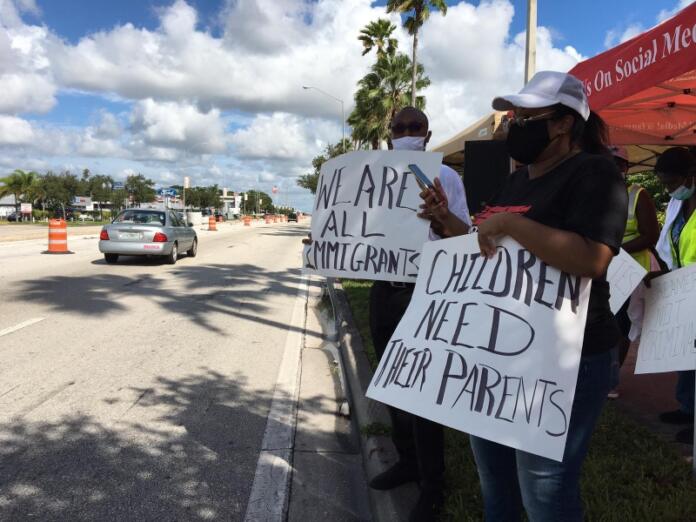

This past September, an appeals court opened the way to end TPS on March 4, 2021. In October, Bastien, with a group of protestors, rallied in front of the Citizenship and Immigration Services Office in Miami to support an extension of the program, and for recipients to be given a pathway to citizenship. If neither happens, deportations could begin.

This crisis speaks to how Caribbean-Americans and other immigrants have been uniquely impacted by the global pandemic. Many in this group have been deemed “essential” workers — a lifeline for the high risk or more privileged among us — yet federal officials have blithely moved to deport them.

“They are our teachers, our organizers, our doctors, our nurses and most importantly, they’ve been our essential workers,” said Bastien. “They’ve put their lives in danger to feed us, to [shop for] our food even during the pandemic, and they’ve been dying.”

South Florida freelance editor and writer Carolyn Guniss has been socially distancing since March.